Formulating and Firing a Crystalline Glaze

I am writing this blog post whilst firing a crystalline glaze so I will be rushing out to the kiln shed every 30 minutes or so. Hopefully you won't be distracted by my regular brief disappearance!

The fact that I am firing at all today does show that I have a working electric kiln again, in fact both are now "clothed and in their right minds" as the Good Book would say! The kiln that has a new contactor is cooling down after a regular stoneware firing that it did two days ago with the help of the controller, and the smaller manually controlled electric kiln is the one doing the crystalline glaze firing, its second since changing the elements.

There was a frost overnight and Laura excitedly called my attention to an icicle that had grown on the rim of a bucket that had been left under the garden hose. Dripping at a rate of one drip every two seconds or so the water had frozen into an stalagmite that was about 4 inches high!

Firing crystalline glazed pots is different to other firings. There are two very important targets to fire to, the first is the peak temperature, currently I am firing to Orton Cone 9, and this is followed by a lower temperature that is likely to be around 1100 Celsius (2012F) which may be maintained for several hours to grow the crystals.

In this blog post I will touch on the first of those two temperatures, the peak temperature. I will say more about the second important temperature, the one where the crystals have a chance to grow, in a separate post.

Several things determine how many crystals grow on the pot that is fired in the kiln, here are some of them:

1) Clay body used to make the pot

2) the glaze recipe

3) glaze thickness

4) the peak temperature of the firing

5) how quickly the kiln fired to temperature

6) how long the kiln is held at peak temperature

The first three items are taken care of before the pot goes in the kiln!

1) The clay body needs to be low in iron, fine textured, and mature at a temperature appropriate to the glaze, some crystalline glaze potters would go for a clay body that matures 2 cones above that of the glaze, because the alkaline crystalline glaze is an aggressive flux. Really the choice is between a porcelain body, or white stoneware. A coarse texture will "irritate" the glaze enough to cause numerous unwanted small crystals to form over the course of the firing. A crystalline glaze is highly caustic and will attack the clay body when at high temperature, some clay formulations may leach out flux or alumina and have a detrimental effect on the ability to make crystals. You really have to experiment to see what will work.

2) The glaze recipe. The majority of crystalline glaze recipes that are in popular use are based on glaze frits. High sodium Frit 3110 is often used. Frit based crystalline glaze recipes are generally rather simple. A cone 9 - 10 glaze base

Frit 3110 50

Silica 25

Zinc Oxide 25

is where many recipes begin, and if you look at a few dozen of them, you will detect that most are variations on this.

A glaze may have a small amount of china clay added, probably between 0.5 and 1.5 percent to add just a trace of alumina to help to control glaze flow and crazing. Or there may be an additional flux added to lower the maturing temperature, you might see Lithium carbonate, talc, or dolomite in some recipes for this.

1 - 3 percent of Titanium dioxide or Rutile may be added to a crystalline glaze base recipe to help stimulate crystal growth. Larger amounts can make a glaze opaque.

Zinc oxide may be as low as 20 percent or as high as 30 percent, this figure is one that can be adjusted to control crystal growth on different clay bodies and for different temperatures.

Just to confuse things further..... the various metal oxides that can be added to the crystalline glaze base to give an attractive palette of colours have an effect on how fluid the glaze is. Copper and cobalt may make the glaze more fluid, where as nickel could have the opposite effect.

Silica also can appear to be as low as 14 percent in some recipes, but be aware that silica can be supplemented by adding china clay, bentonite, talc, frit, feldspar and so on, so the silica percentage in the recipe might not tell the whole story, you really need to see the glaze formula to understand what is in it more clearly. Someone wrote that silica is like "water" in which the crystals form, and you need enough of it for that to happen. I thought that was a rather nice analogy.

There are other ways of making crystalline glazes. I also enjoy crystalline glazes that use feldspar to supply the primary flux instead of relying on a glaze frit, and there are some that work well, if a little temperamentally.

What ever the formulation I always add 1 - 2 percent of bentonite to my crystalline glazes, it really makes a great difference in how the glaze behaves in the glaze bucket, its ease of application, and how firmly it stays attached to the pot before it is fired.

3) Glaze thickness influences crystal growth. Too thin gives "nowhere" for the crystals to grow, and they are too much affected by the clay body so you get thousands of them.

Too thick can yield too few crystals on a vertical surface or a mass of coarse "sand paper" in a pool in the bottom of a bowl where the three dimensional crystals have grown strongly upward as well as outward.

"Just right", will allow for good sized crystals to grow surrounded by some space.

I mostly brush on crystalline glazes (I have sprayed them and also dipped and poured them in the past). I apply at least three or four thick coats on the top third of the pot tapering to two coats near the foot.

To apply with a brush I make my glaze with 1000 g of dry ingredients to 650 - 700 g of water.

5) How quickly the kiln fires. In my previous post I mentioned how important it was to have elements in good condition when firing crystalline glazes. In spite of accurately firing to cones, cone 9 reached rapidly will give a different result to cone 9 that has been reached slowly. It may be that the aggressive nature of the alkaline glaze has something to do with this, as a long while spent at high temperature gives more opportunity for glaze to interface with clay body. What ever the reason, it gets harder to grow nice crystals if the kiln reaches temperature too slowly. I suspect that this is especially the case with frit based glazes that go into a fluid state much earlier in the firing than a feldspar based glaze.

6) How long the kiln is held at peak temperature. It may seem counter intuitive to hold the kiln at peak temperature after being in such a rush to get there, but a hold here can help fine tune how many crystals remain on the pot. What is happening here is that surplus glaze is flowing off the pot, (yes you did remember to fire with a glaze catching bowl!?) and also more of the zinc is going into solution.

A simple Glaze and Schedule

Well, after all that, my head is buzzing, and you may be asleep or have run away! For those who have stayed the distance I hope this little introduction does show some of the many variables and complexities involved in firing this sort of glaze. Those determined to give it a go should definitely have a try, and the following recipe will give you something to play with at cone 9 - 10

50 Frit 3110

25 Silica

25 Zinc oxide

3 Titanium dioxide

2 Bentonite

A simple firing schedule would be

Fire to cone 9 in 8 or 9 hours

Switch off

On again when kiln is at about 1100 Celsius (2012F)

Hold for 3 hours

Kiln off

Use porcelain or a smooth white stoneware.

Protect kiln shelves, take note of my previous post where I have written about glaze catching bowls and rings.

Apply the glaze thickly.

Record your firing hourly, or more frequently, on graph paper.

Good Luck!

Well I am nine hours into my firing as I finish this episode of the blog. We hit peak temperature an hour ago, and now I am half an hour into the long hold at around 1100 Celsius (2012F) where crystals will have the time to grow to a good size. You can generally count on an average of about 10mm per hour of crystal growth at this temperature, and I will aim to grow these for 4 and a half hours.

The fact that I am firing at all today does show that I have a working electric kiln again, in fact both are now "clothed and in their right minds" as the Good Book would say! The kiln that has a new contactor is cooling down after a regular stoneware firing that it did two days ago with the help of the controller, and the smaller manually controlled electric kiln is the one doing the crystalline glaze firing, its second since changing the elements.

There was a frost overnight and Laura excitedly called my attention to an icicle that had grown on the rim of a bucket that had been left under the garden hose. Dripping at a rate of one drip every two seconds or so the water had frozen into an stalagmite that was about 4 inches high!

|

| Ice stalagmite. |

Firing crystalline glazed pots is different to other firings. There are two very important targets to fire to, the first is the peak temperature, currently I am firing to Orton Cone 9, and this is followed by a lower temperature that is likely to be around 1100 Celsius (2012F) which may be maintained for several hours to grow the crystals.

In this blog post I will touch on the first of those two temperatures, the peak temperature. I will say more about the second important temperature, the one where the crystals have a chance to grow, in a separate post.

Several things determine how many crystals grow on the pot that is fired in the kiln, here are some of them:

1) Clay body used to make the pot

2) the glaze recipe

3) glaze thickness

4) the peak temperature of the firing

5) how quickly the kiln fired to temperature

6) how long the kiln is held at peak temperature

The first three items are taken care of before the pot goes in the kiln!

1) The clay body needs to be low in iron, fine textured, and mature at a temperature appropriate to the glaze, some crystalline glaze potters would go for a clay body that matures 2 cones above that of the glaze, because the alkaline crystalline glaze is an aggressive flux. Really the choice is between a porcelain body, or white stoneware. A coarse texture will "irritate" the glaze enough to cause numerous unwanted small crystals to form over the course of the firing. A crystalline glaze is highly caustic and will attack the clay body when at high temperature, some clay formulations may leach out flux or alumina and have a detrimental effect on the ability to make crystals. You really have to experiment to see what will work.

2) The glaze recipe. The majority of crystalline glaze recipes that are in popular use are based on glaze frits. High sodium Frit 3110 is often used. Frit based crystalline glaze recipes are generally rather simple. A cone 9 - 10 glaze base

Frit 3110 50

Silica 25

Zinc Oxide 25

is where many recipes begin, and if you look at a few dozen of them, you will detect that most are variations on this.

|

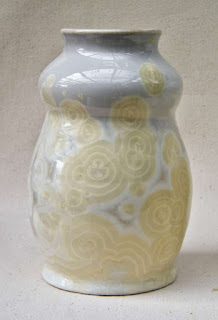

| This is an example of a very simple glaze that is based on the 50:25:25 recipe above. |

1 - 3 percent of Titanium dioxide or Rutile may be added to a crystalline glaze base recipe to help stimulate crystal growth. Larger amounts can make a glaze opaque.

|

| Titanium dioxide in this glaze gives cream coloured crystals on a cold white background. |

|

| Rutile as an opacifier gave shell-like orange, pink and cream colour. |

Zinc oxide may be as low as 20 percent or as high as 30 percent, this figure is one that can be adjusted to control crystal growth on different clay bodies and for different temperatures.

Just to confuse things further..... the various metal oxides that can be added to the crystalline glaze base to give an attractive palette of colours have an effect on how fluid the glaze is. Copper and cobalt may make the glaze more fluid, where as nickel could have the opposite effect.

|

| Nickel oxide has the peculiar ability to give blue crystals with an orange background in a crystalline glaze. |

Silica also can appear to be as low as 14 percent in some recipes, but be aware that silica can be supplemented by adding china clay, bentonite, talc, frit, feldspar and so on, so the silica percentage in the recipe might not tell the whole story, you really need to see the glaze formula to understand what is in it more clearly. Someone wrote that silica is like "water" in which the crystals form, and you need enough of it for that to happen. I thought that was a rather nice analogy.

There are other ways of making crystalline glazes. I also enjoy crystalline glazes that use feldspar to supply the primary flux instead of relying on a glaze frit, and there are some that work well, if a little temperamentally.

|

| These complex crystals were grown in a feldspar based glaze. |

3) Glaze thickness influences crystal growth. Too thin gives "nowhere" for the crystals to grow, and they are too much affected by the clay body so you get thousands of them.

|

| One and two coats of glaze on this sample. See how rough the glaze looks on the lower left of the photo where it is too thin. There are thousands of small crystals here. |

Too thick can yield too few crystals on a vertical surface or a mass of coarse "sand paper" in a pool in the bottom of a bowl where the three dimensional crystals have grown strongly upward as well as outward.

"Just right", will allow for good sized crystals to grow surrounded by some space.

|

| Cobalt blue coloured crystals on a pale background. |

I mostly brush on crystalline glazes (I have sprayed them and also dipped and poured them in the past). I apply at least three or four thick coats on the top third of the pot tapering to two coats near the foot.

|

| Brushing a glaze, use a large soft brush that holds lots of glaze. |

To apply with a brush I make my glaze with 1000 g of dry ingredients to 650 - 700 g of water.

4) The Peak Temperature of the firing, this is crucially important. Always use cones to determine this. Small variations, a mere 5 degrees or so, will make a noticeable difference in how many crystals cover the pot. If you fire at too low a temperature there will be far too many crystals that might even feel rough or dry. If you fire too high you will be left with few if any crystals. Just right, is a matter of taste.

|

| Large crystals with plenty of space around them. |

Large crystals can look very impressive if they are surrounded by plenty of "empty" glaze, but crystals that cover a pot can also be spectacular.

|

| Crystals covering a vase and looking spectacular! |

5) How quickly the kiln fires. In my previous post I mentioned how important it was to have elements in good condition when firing crystalline glazes. In spite of accurately firing to cones, cone 9 reached rapidly will give a different result to cone 9 that has been reached slowly. It may be that the aggressive nature of the alkaline glaze has something to do with this, as a long while spent at high temperature gives more opportunity for glaze to interface with clay body. What ever the reason, it gets harder to grow nice crystals if the kiln reaches temperature too slowly. I suspect that this is especially the case with frit based glazes that go into a fluid state much earlier in the firing than a feldspar based glaze.

6) How long the kiln is held at peak temperature. It may seem counter intuitive to hold the kiln at peak temperature after being in such a rush to get there, but a hold here can help fine tune how many crystals remain on the pot. What is happening here is that surplus glaze is flowing off the pot, (yes you did remember to fire with a glaze catching bowl!?) and also more of the zinc is going into solution.

|

| Glaze run off into the catching bowl. |

A simple Glaze and Schedule

Well, after all that, my head is buzzing, and you may be asleep or have run away! For those who have stayed the distance I hope this little introduction does show some of the many variables and complexities involved in firing this sort of glaze. Those determined to give it a go should definitely have a try, and the following recipe will give you something to play with at cone 9 - 10

50 Frit 3110

25 Silica

25 Zinc oxide

3 Titanium dioxide

2 Bentonite

A simple firing schedule would be

Fire to cone 9 in 8 or 9 hours

Switch off

On again when kiln is at about 1100 Celsius (2012F)

Hold for 3 hours

Kiln off

Use porcelain or a smooth white stoneware.

Protect kiln shelves, take note of my previous post where I have written about glaze catching bowls and rings.

Apply the glaze thickly.

Record your firing hourly, or more frequently, on graph paper.

Good Luck!

Well I am nine hours into my firing as I finish this episode of the blog. We hit peak temperature an hour ago, and now I am half an hour into the long hold at around 1100 Celsius (2012F) where crystals will have the time to grow to a good size. You can generally count on an average of about 10mm per hour of crystal growth at this temperature, and I will aim to grow these for 4 and a half hours.

Bye for now!

Comments

Well done on all this research and work and fascinating discovery.

I do sometimes wonder about "That Book"... I do tend to go on far to long for a blog when I get started! :-)

Hi Linda,

Thank you for sticking with refreshing the page, I'm sorry that it was slow to download for you. I try to keep the size of the photos very small to help them arrive easily, but the internet is a mysterious thing! Glad you enjoyed the photos once they arrived!

Nice to hear from you. Looking forward to catching up again in person!

:-)

A great description of the crystalline glaze process which I will share with my fellow potters. Stay warm this winter.

Yes it is good to be Covid free (for now anyway!), quite a shake up to our health system just getting ready for it. Hopefully, with the experience gained from this episode, we will be in better shape now to deal with it if it gets to us in any numbers again.

I hope to get the next part of this glaze firing series of blog posts out in the next few days.

All the best,

Peter

I see you have been busy. What amazing crystals! I can see the passion in those pots. Hope you and Laura are doing fine in during the Covid-19 pandemic.

All the best,

Sandie

Lovely to hear from you. Laura and I are doing OK regards the pandemic as NZ is almost free of it currently, but there certainly were a lot of day to day changes to how we live life all through the time of "lock down" that we had. The peace and quiet of full lock down when there was little traffic on the road, and we made bread, really appreciated vegetables from our garden, and rarely went to the shop, was like stepping back in time.... even the birds started coming inside the house! Not sure how NZ is going to re-connect with the rest of the world again, it is quite dilemma, but our isolation is keeping us safe for now!

Hope things going OK for you?

All the best,

Peter & Laura

Crystalline glazes usually require lots and lots of careful, patient work and many experiments to get them to work well. Whilst the glaze recipes are often quite simple, the firings need to be accurate and well controlled, your comment about the kiln "topping out at 1100 maybe 1150" (which I am guessing to be about cone 1 to cone 4) indicates to me that you may not quite understand just what is involved.

I haven't done any crystalline glazes at the relatively low temperature that you are firing to, mine have all been Cone 8 - 10, but I do know that there are potters working with crystalline at Cone 6, 1220 - 1240, and some of their recipes are similar to cone 10 ones, but have an addition of Lithium carbonate added (2 - 5 percent) to drop the maturing temperature.

It may be possible to lower the maturing temperature even further by the addition of more lithium and another flux, such as Gerstley borate, but I have not tried anything like that myself.

I would suggest visiting glazy.org and looking at the glaze recipes on that site. There is a vast selection of interesting glazes for a wide range of temperatures, there might be something that appeals to you there and that would work well with your sculpture.

Sorry not to be more help,

Peter

I will be experimenting with crystalline glazes this summer and this post has helped me quite a bit. If possible I was wondering if you could answer a few questions of mine?

When firing to temperature I have seen many different techniques and was wondering what the benefits are of each. Some fire to a hot cone 10 and ramp down the speed as they approach temperature with no hold. Others seem to fire to a cone 9 with a 5-15 minute hold at temperature. I assume that they both allow glaze to run off the pot, but was curious about the differences. Which method might be better for a first firing?

Secondly, I was interested in what it takes to achieve a gray/blue crystalline glaze. Many sources say that manganese and cobalt will give the desired color, but I have not found any sources that give exact percentages. I understand if you might not want to share this though.

Lastly, do you believe it is possible to get decent crystalline results in a wood kiln? I understand that holding a wood kiln at certain temperatures is difficult, and I do not plan on trying out a crystal glaze in this type of kiln. However, it seems like you have a good amount of experience with wood kilns and crystal glazes, so I was wondering if you had ever tried this out.

Thank you for this great post,

-Philip

You ask some very good questions, and I will do my best to help if I can!

Regarding the cone 9 or 10, and how fast to get there and how long to hold there... I think that several things feed into the decision making for that point in the firing.

1) the performance of the kiln. My kilns are very old and have a layer of insulating brick backed with a thick layer of fibre. I have rather heavy kiln furniture, and, whilst my kilns will get to cone 10, they do climb quite slowly through the last part of the firing, this can make for difficulties with crystalline glaze firings, and in recent years I have tended to try to formulate glazes that will mature from about cone 8.5 to cone 9 rather than cone 10.

I know that there are electric kilns that are designed specifically for crystalline glaze firing, that are very powerful, have low thermal mass, and can heat and cool quickly, so they may well fire rapidly to cone 11 and have the capacity to adjust ramps and holds to fine tune what is happening to their glazes. Some potters say they get better results with new kiln elements and very fast firings to peak temperature.

My situation demands that I have to adapt to what is possible with my kiln, rather than having the power and performance available to dictate.

The purpose of getting to the temperature is mostly about controlling the number of crystals that you end up with on the pot. Excess heat, soaks, or slow progress of the kiln will tend to reduce the number of crystals.

On a first crystalline glaze firing, I would keep the firing as simple as possible and also choose fairly uncomplicated glaze recipes. If I want to fire to cone 9, I would fire at a normal rate of climb for a stoneware firing until the kiln is at a dull red heat, then fire as fast as the kiln will go until it reaches cone 9 then switch off! Allow the kiln to drop to 1100 Celsius (2012 F), then hold 1100 for 1 hour. Then switch off the kiln.

The one hour hold should give crystals that are up to about 1 cm (1/2 inch) in size... if they are going to work at all!

Once the kiln is unpacked, have a good honest look at each test piece (and they will all be tests for the next few firings). If crystals have formed, then try again and see what effect soaking from cone 8 down to cone 9 down has. Also extend the hold at 1100 C (2012F) to 3 hours and note the result.

(If no crystals developed in the first firing, but the glaze was very glassy and ran a lot, then you may need to aim for a cone 8 peak temperature next time.)

Manganese does tend toward gray colours in crystalline, especially with cobalt. You could try as little as 0.5% cobalt carbonate to 1 - 2 manganese and expect some blues and grays. You would get a stronger blue with cobalt oxide. Lovely things can be done with copper and cobalt, or manganese, cobalt and copper. I sometimes make up enough glaze base to then divide into 3 or 4, and add different oxides to each (about 1 - 2 percent will do). Then I can combine them together as I feel inspired rather than doing further measuring.

The problem with a wood kiln and crystalline is not so much the lack of control, but the reducing atmosphere. Zinc is sensitive to reduction and there is lots of it in a crystalline glaze. A little reduction at certain points in a crystalline firing can do wonderful things, but it could also easily give you something that ended up blistered, gray and rather like the surface of the moon!

I did try firing crystalline in the wood kiln by accident once, and got a very interesting little pot. Not obviously crystalline, but with a lovely surface!

Let me know how you get on with your experiments!

Peter